Get Tech Tips

Subscribe to free tech tips.

Why the 20° Rule is Driving The Internet Crazy

Every year when outdoor temperatures rise, there is a rash of news stories and articles about air conditioning. We had an early heatwave this year, and many people have come out and referred to the idea of a rule of thumb of what temperature you can achieve indoors based on the outdoor temperature; most commonly used is the “20° rule.” Here is a link to an article like this.

There is no such thing as a universal 20° rule. It is simply the difference between indoor and outdoor design conditions, and it varies based on location and design.

There are times where 20° is the design difference between indoor and outdoor temperatures, specifically when the design outdoor temperature is 95°, and indoor is 75° for cooling. Before we go any further, let's specify EXACTLY what we are talking about.

We're talking all about designing an air conditioning system, and this discussion has nothing to do with DIAGNOSING it. Whenever a technician goes to a home, their job is to diagnose and test the HVAC system, not quote rules of thumb.

HOWEVER…

When a contractor designs an air conditioning system, they have to size it for the space being cooled (I'm just going to focus on cooling here). The size of the unit needs to be based on a design indoor and outdoor temperature and humidity.

ACCA fixes the indoor temperature design for homes at 75°, and the designer can choose 45%, 50%, 0r 55% indoor design humidity.

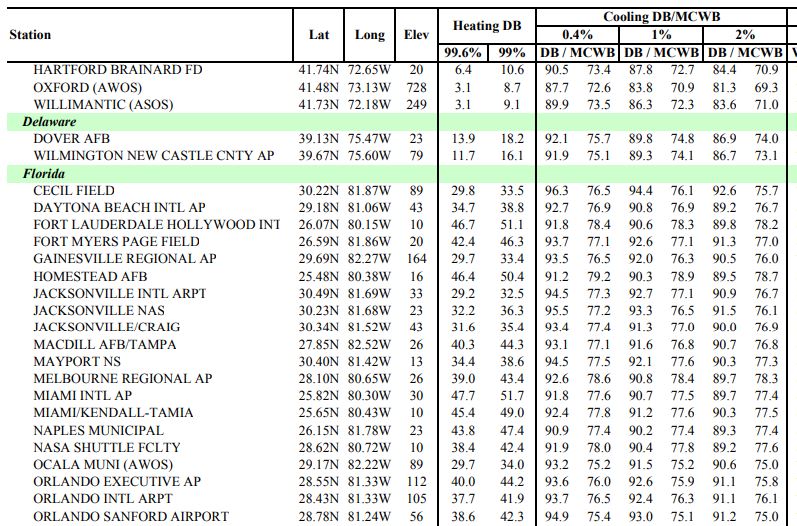

The outdoor design temperature comes from temperature data specific to the location. It is based on a temperature that will only be (statistically) exceeded 1% or 0.4% of the time in that location.

We do not design air conditioning systems for the hottest possible day with the lowest possible indoor temperature the customer may want because that would result in over-sizing for 99.6% of the year, and oversizing isn't a good thing for many reasons, including:

- Higher initial cost

- Larger ducts required

- Poor humidity control

- Short-cycling, resulting in less efficiency and shorter system life

- Generally lower-rated efficiency on larger capacity systems

Take a look at the chart above, and you can see from a glance that Florida has outdoor design conditions of 90° to 95°, depending on the city and which column you use for design. Because the indoor design conditions stay fixed at 75° regardless, the design difference on a peak design day varies from 20° down to as low as 15°.

Nevada (for example) is completely different:

You can see Reno is much like Florida in terms of dry-bulb temperature, but Las Vegas is 106°-108° and still a 75° indoor temperature design, so engineers have to design a unit for a 31° to 33° difference.

ACCA Manual J does allow some oversizing to find a proper system match, up to 15% greater than the load for straight cooling and 25% greater on heat pump systems (where the heating load is greater than the cooling load), but that isn't a lot of wiggle room.

It's also important to remember that system performance also changes based on outdoor and indoor temperatures. We must select our equipment capacity based on the specific design conditions rather than AHRI conditions, 80° indoor and 95° outdoor temperatures.

So, here are some facts to get straight:

- There is no universal design rule of thumb.

- This 20° rule has no relationship to the old 20° delta T rule (which is also a bad rule of thumb).

- Oversizing isn't a good idea, ESPECIALLY in humid climates.

- The fact that you can get your home to a certain temperature in one part of the county has nothing to do with another location.

- How cold you can get your house on a hot day is just a representation of your system's capacity compared to the load; it's not something to be proud of.

- Did I mention that oversizing isn't a good thing? Just because you can get your house to 66° on a 140° degree day in Nome, Alaska, doesn't mean you have a better air conditioner. It means someone put in a unit that is much too large.

So, when a contractor emails their clients before a heatwave (as I did recently) or when a LOCAL news channel runs a story and quotes something like, “You can expect your home to maintain only 20° lower inside than the outdoor temperature,” withhold judgment for a minute and consider this: That 20° rule may be a good guideline for their market, and they may be telling it to consumers to reduce nuisance service calls on a rare 100° day in a place like Savannah where the design temperature is 93°.

As HVAC professionals, we understand that some designs will do better than others, and with modern multi-stage/variable speed systems, we can get away with a little more oversizing than we used to. We also (should) know that we size systems based on heat gain and loss, not based on square footage and that oversizing a system because the customer wants it like a “meat locker” has unintended consequences.

Now, there will always be the techs who use silly rules of thumb rather than proper diagnostic procedures. If a customer calls you to look at their A/C, don't just walk up to the thermostat and say something like, “It's 80° in here and 100° outside, so it's doing good.” You need to test the equipment properly, and I would suggest doing actual capacity calculations using in-duct psychrometers and MeasureQuick in addition to everything else if it seems like the system just isn't keeping up.

Check the charge, check ducts and insulation, and do a good job of making sure everything is as it should be for the customer—but sometimes, on unusually hot days, a properly designed and installed system may not maintain 75° inside.

So, these are my takeaways:

- Size systems properly, not based on rules of thumb.

- Still use proper system diagnosis and commissioning. Don't use a rule of thumb as an excuse not to make a proper diagnosis.

- It's OK to use a rule of thumb specific to your market to communicate with customers so long as it's based on real design conditions.

- Don't oversize systems, especially in humid climates.

- Don't be a jerk to people on the internet.

So, in Orlando, you can expect your A/C to maintain 75° on a 95° day in most cases. If the temperature rises above that, it may not keep up.

—Bryan

If you want to know more about the ACCA design process, take a look at this quick sheet with design instructions.

Comments

Always appreciate your articles, but this one has me baffled…

As a designer, reading your ‘the designer can choose 45%, 50% 0r 55% indoor design humidity,’ what or how are you coming up with that? An HVAC system is not a dehumidifier, so these results will never happen, or are an arbitrary ACH(50) is being made, the building has no insulation, ducts are not sealed, many questions on this one. Worse case, I would suggest a leakage report be completed.

Though, as one that provides the different Manual Designs, want to thank you for commenting on the specific design conditions of peak hour per code; suggestion would be to explain the partial loads that no one thinks about.

Greatly appreciate that you mention not using the old ‘rule-of-thumb!’ The orientation and thermal envelope are what is needed, not the generic square footage.

Depending on the HVAC system, capacity, efficiencies and the air handler settings with its match condenser can have many different results. Like many consumers, price is a big factor, so while I agree with full variable capacity, separate zonings can be beneficial, but most are not willing to pay the additional amounts for better control of temperature and some humidity control.

If humidity is a concern, a whole house dehumidifier should be discussed.

Otherwise, when I hear the twenty degree amount, it is usually referenced to the indoor “Leaving Coil Delta-T,” rather than outside temperatures.

Always appreciate your articles, but this one has me baffled…

As a designer, reading your ‘the designer can choose 45%, 50% 0r 55% indoor design humidity,’ what or how are you coming up with that? An HVAC system is not a dehumidifier, so these results will never happen, or are an arbitrary ACH(50) is being made, the building has no insulation, ducts are not sealed, many questions on this one. Worse case, I would suggest a leakage report be completed.

Though, as one that provides the different Manual Designs, want to thank you for commenting on the specific design conditions of peak hour per code; suggestion would be to explain the partial loads that no one thinks about.

Greatly appreciate that you mention not using the old ‘rule-of-thumb!’ The orientation and thermal envelope are what is needed, not the generic square footage.

Depending on the HVAC system, capacity, efficiencies and the air handler settings with its match condenser can have many different results. Like many consumers, price is a big factor, so while I agree with full variable capacity, separate zonings can be beneficial, but most are not willing to pay the additional amounts for better control of temperature and some humidity control.

If humidity is a concern, a whole house dehumidifier should be discussed.

Otherwise, when I hear the twenty degree amount, it is usually referenced to the indoor “Leaving Coil Delta-T,” rather than outside temperatures.

This is where inverter systems win.

This is where inverter systems win.

To leave a comment, you need to log in.

Log In