Nikki Krueger – The Dripping Point

February 24, 2020

Sensible load refers to the temperature we can feel, and latent load refers to the moisture in the air. Dehumidifiers focus on addressing the latent load, and water pulled from the air may be measured in pints or pounds (which are the same thing). Relative humidity shows the percentage of humidity based on the temperature; if we heat up the air but maintain the same amount of water vapor in the air, the relative humidity will drop. When the relative humidity hits 100%, it reaches the dew point, and condensation happens. We want to limit condensation on surfaces because it may lead to microbial growth.

Colder evaporator coils and longer runtimes can help us regulate the latent load and remove excess moisture. However, the houses we build nowadays are a lot tighter and are not designed to breathe, so we also need to be aware of sources of infiltration (especially when exhaust-only ventilation is used) and oversized systems with short runtimes, which may also affect indoor humidity. There is even a new ACCA manual (LLH) for the low-load homes being built to the current code requirements. Dehumidifiers may also help, and those work particularly well in shoulder seasons.

Throughout the day, sensible loads tend to vary more than latent loads, so we need to focus on the dew point to control condensation at all parts of the day, not just when the A/C is running. Higher relative humidities lead to VOC off-gassing and allow microbes to survive, so controlling relative humidity can make a home much healthier, especially if we aim for around 50% relative humidity.

In many cases, we design houses for the peak heat load, which represents only 1% of the time. As a result, the HVAC runtimes don’t reach the point where the equipment can dehumidify the air effectively (if at all). Energy-efficient equipment also tends to have poor dehumidification. Lower-SEER systems tend to have larger coils that can get quite cold, so the coils can pull a lot more moisture out of the air. To determine the effectiveness of a system’s dehumidification, we need to look at the sensible heat ratio (SHR). Lower sensible heat ratios indicate better dehumidification, and we can achieve those lower SHRs with longer runtimes. Otherwise, the moisture will just go back into the home.

A whole-house ventilating dehumidifier can dehumidify the home separately from the HVAC system by using a dedicated return. These dehumidifiers can also meet ventilation requirements in some areas. Sometimes, people use ERVs for ventilation; ERVs cross airstreams and exchange moisture to lessen the latent load, but they aren’t very effective when the airstreams are equally humid. Whole-house dehumidification has demonstrated superior performance in Central Florida in case studies. When fresh air enters the equation, the whole-house dehumidifier doesn’t typically dehumidify that air because it’s too energy-intensive for a small amount of fresh air; instead, we can rely on filtration to purify that outdoor air.

The recommended whole-house ventilating dehumidifier installation has a dedicated return to the HVAC supply. When there is no existing ductwork, such as when you have ductless mini-splits, you will have to add some ductwork and distribute the incoming air into about three areas with ductless heads. The return-to-return installation is a poor dehumidifier configuration in Florida. Even though return-to-return installations may be better for accessibility in some cases, the installation is energy-intensive and may even result in higher relative humidity.

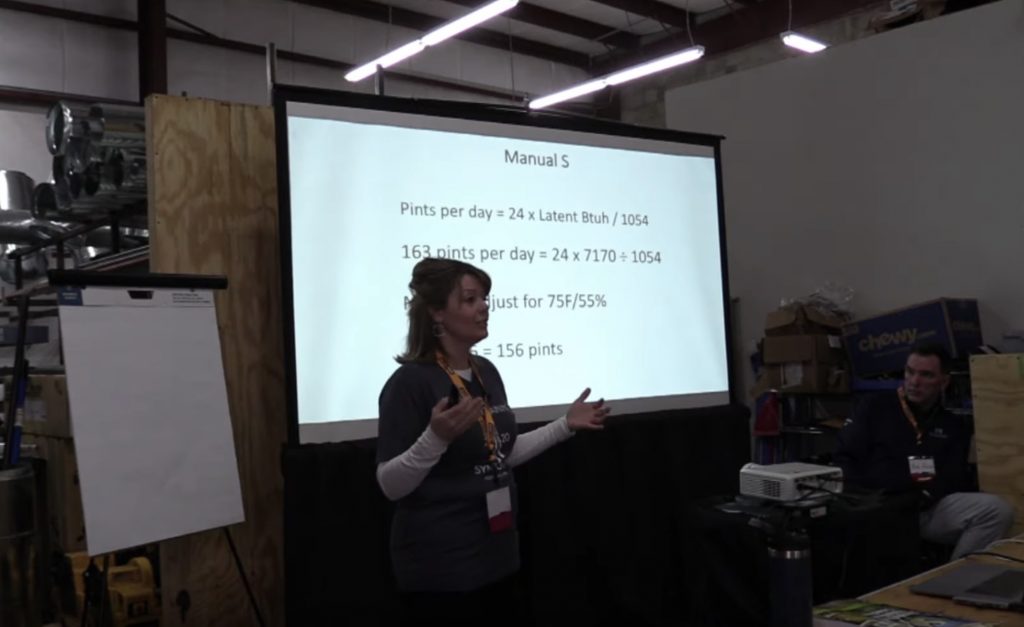

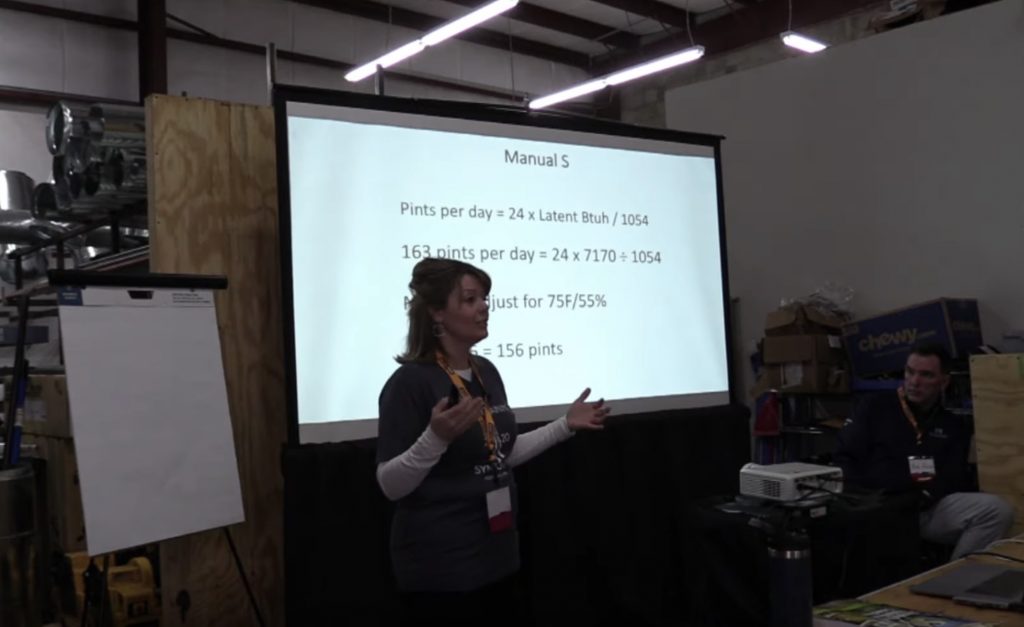

You can use a mobile app to determine how much dehumidification a home needs. Occupancy and load conditions also affect indoor relative humidity and must be considered. To size a dehumidifier correctly, we need to know how much moisture the HVAC unit removes, how the unit is sized, how often the unit runs at the conditions used for sizing, and if we’re using fresh air ventilation. From there, you can use Manual J calculations to size a dehumidifier. Once you figure out how many pints you will need to remove per day, you can use Manual S calculations to pin down an exact unit and design.

Santa Fe has also developed in-wall dehumidifiers, which are great for applications that don’t have room for ducted dehumidifiers. Drainage is important to consider in all types of dehumidifiers, and drain traps should be accessible for easy cleaning.

There is also some discussion about ventilation and latent load control on the commercial side of HVAC as well as who is responsible for dehumidification.

Comments

Awesome presentation. I am a builder of very tight energy efficient homes in coastal NC (.5 ACH50 and below). Everything you cover is what I have been trying to get across to customers and other builders down here. Spot on. I include a dedicated dehumidifier in every home that runs independent of the HVAC system to ensure humidity control year-round. In addition, we encapsulate the entire building, crawlspace and attic with closed cell foam. For makeup air (never want house to go negative, ever.) I have added a six inch vent into attic, with an inline blower that is temperature and humidity limited so that is does not run at extremely high or low temperatures or high outside humidity. This air is mixed with the already conditioned attic air and then introduced into the main living space via a dehumidifier return branch. We now have positive airflow that can leave via the bath vents and other routes as needed. We keep RH at around 45% year-round this way. This is a very inexpensive solution to a serious problem. Costs around $2000+ to implement.

Awesome presentation. I am a builder of very tight energy efficient homes in coastal NC (.5 ACH50 and below). Everything you cover is what I have been trying to get across to customers and other builders down here. Spot on. I include a dedicated dehumidifier in every home that runs independent of the HVAC system to ensure humidity control year-round. In addition, we encapsulate the entire building, crawlspace and attic with closed cell foam. For makeup air (never want house to go negative, ever.) I have added a six inch vent into attic, with an inline blower that is temperature and humidity limited so that is does not run at extremely high or low temperatures or high outside humidity. This air is mixed with the already conditioned attic air and then introduced into the main living space via a dehumidifier return branch. We now have positive airflow that can leave via the bath vents and other routes as needed. We keep RH at around 45% year-round this way. This is a very inexpensive solution to a serious problem. Costs around $2000+ to implement.

https://bestiptvservice.vip

https://bestiptvservice.vip

To leave a comment, you need to log in.

Log In