Get Tech Tips

Subscribe to free tech tips.

Subcooling vs. Liquid Line Temperature

There is a common belief in the trade that the higher the subcooling, the better the system efficiency because lower liquid line temperature means less flash gas.

This statement is only partially true and can lead to some confusion among techs.

Subcooling is a temperature decrease below the condensing temperature of the refrigerant that occurs once the refrigerant is 100% liquid. Our objective is to provide subcooled liquid to the metering device at the lowest temperature possible while maintaining the minimum pressure drop required across the metering device.

We do not want to accomplish high subcooling by artificially driving up the condensing temperature unless there is no other option to provide the minimum pressure drop across the metering device.

The “subcooling is the answer” mistake occurs when a technician overcharges a system to get a higher subcooling number at the expense of higher head pressure rather than lower liquid temperature.

The condenser's job is to reject heat from the refrigerant to the condensing medium (generally air); the liquid temperature cannot drop below the temperature of whatever it is rejecting its heat to. So, as refrigerant is added to a system, the quantity of liquid contained in the condensing coil increases, resulting in a higher subcooling number but ALSO resulting in higher head pressure, condensing temperature, and compression ratio.

As more refrigerant is packed into the condenser coil, there may be some decrease in liquid line temperature. However, much of the increased subcooling will come from an increase in condensing (liquid saturation) temperature rather than actually cooler liquid.

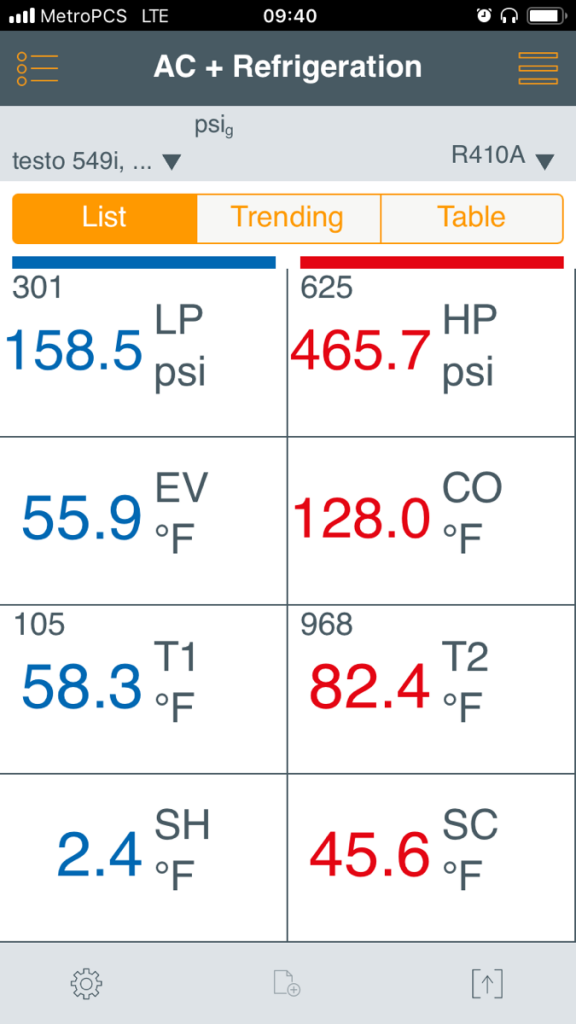

Take a look at the system readings above. The outdoor temperature was 80°, and the liquid temperature was 82.4°, but the head pressure and subcooling were astronomically high due to a severe overcharge.

The liquid line temperature was limited to just above the outdoor temperature. As more and more refrigerant was added to the system, the head pressure (and, therefore, the condensing temperature) was going sky-high, resulting in poor system efficiency.

While it is true that a lower liquid line temperature entering the metering device does reduce the amount of “flash gas” converted directly from liquid to vapor as it leaves the metering device, this is not an efficiency gain when the subcooling is artificially increased due to overcharging or other methods of increasing head pressure.

—Bryan

Comments

I came across this the other day.

410a system. Txv.

Low subcooling. High superheat.

Figured it was low, put about 3 pounds in and subcooling never went up, super heat went down.

Temp dif was better, but not great. I was thinking I had a restriction or bad txv, but I’m still learning and didn’t really have a clue.

I came across this the other day.

410a system. Txv.

Low subcooling. High superheat.

Figured it was low, put about 3 pounds in and subcooling never went up, super heat went down.

Temp dif was better, but not great. I was thinking I had a restriction or bad txv, but I’m still learning and didn’t really have a clue.

This is very interesting, You’re an excessively professional blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to looking for extra of your magnificent post. Also, I’ve shared your web site in my social networks

This is very interesting, You’re an excessively professional blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to looking for extra of your magnificent post. Also, I’ve shared your web site in my social networks

To leave a comment, you need to log in.

Log In