Get Tech Tips

Subscribe to free tech tips.

Making a Flare – Quick Tips

This article is not a full lesson on making a flare, but it will give you some best practices to make a flare that doesn't leak.

First off, we need to clarify that very few unitary manufacturers use flares anymore. You will most often find flares on ductless and VRF/VRV systems and in refrigeration. A flare uses a flared female cone that's formed into tubing (usually copper). That cone is then pressed onto a male cone (usually brass) by a threaded flare nut. A flare shouldn't be confused with a chatleff fitting that uses a threaded nut and seals with a Teflon or nylon seal. Flares and chatleff fittings are both threaded connections, which is why it's easy to confuse the two. You can learn more about threaded connections by listening to a short HVAC School podcast episode about them HERE.

Best practices for making a flare

- Use proper depth; the old-school method is to bring the copper up a dime's width above the block, but modern flaring blocks usually have built-in gauges that work well.

- Don't trust factory flares. In many cases, factory line-set flares are made poorly; it's often better just to cut them off and start over.

- Ream the copper before flaring to remove the burr, but don't OVERREAM and thin out the copper edge.

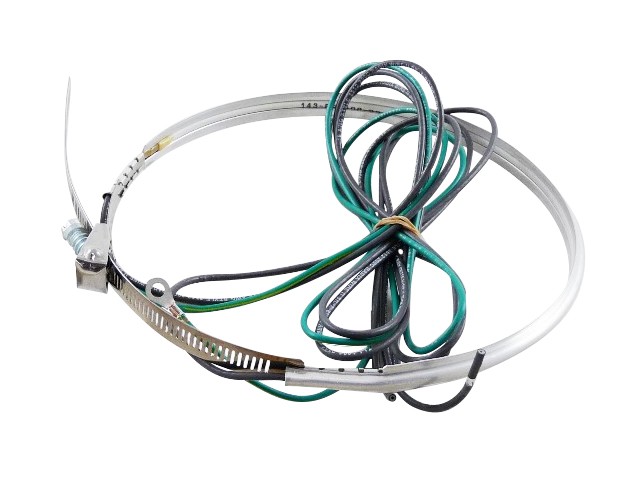

- Use a good, modern flaring tool designed for refrigeration. This is a great one.

- When making the flare, use a bit of refrigerant oil. It's even better to use a bit of Nylog. You only need a drop or two; you can put one drop on the flare while making it to prevent binding and create a smoother flare surface. Put a bit on the back of the flare as well. That way, you can allow the nut to slide easily. I also like one small drop on the threads and spread it to the mating surfaces. It's worth noting, however, that some manufacturers disagree with this due to the effect it has on torque specs. So, I always suggest following their recommendations when in doubt. In my experience, a bit of assembly lubricant really helps.

- Use a flare wrench instead of an adjustable wrench. Then, tighten the flare nut with a torque wrench. I understand that very few techs do this, but it's a great practice if you want to get it right the first time with no leaks or damage. That can be done easily with a set of SAE crowfoot flare nut wrenches and a 3/8″ torque wrench. As always, use manufacturers' torque specs if available. If not, you may use the chart below. Make sure to keep the crowfoot at 90 degrees to the wrench (perpendicular), and place your hand on the end grip of the wrench. If you have lubricant on the threads, stay on the low side of the torque rating.

Using these practices, we have VERY FEW leaks on flare fittings.

Some things NOT to do that I've seen

- Don't use leak lock or Teflon tape on flares.

- Don't over-tighten flares to try and get them to stop leaking. If they are properly torqued and still leak, they are made wrong.

- Don't use too much oil or Nylog; a drop or two will do.

- Don't try and jam a Teflon seal from a chatleff on a flare.

Some other things to note

There is a company called Spin that uses a flaring tool that goes on a drill. Their tool actually heats and anneals the copper. They claim they don't need to get the flare to 45 degrees because the annealing makes the copper soft enough that the nut itself with finish the flare. We have used it a few times with good results.

NAVAC also has a great cordless power flaring tool, the NEF6LM. It's pretty light and easy to use in the field, and you'll get perfect flares as long as you follow the best practices I mentioned above. I filmed a demo and review of the product a while ago, and you can watch that HERE.

There are now companies that make nylon/Teflon (I'm actually not sure what they are made of) gasket inserts that go into a flare. Some techs swear by them. I really don't see the necessity, but I don't have any experience with them.

Finally, make sure to pressure test to the rated test pressure when your system has flares, and bubble test the joints. Then, perform a vacuum to below 500 microns and decay test. You can follow the steps below, and that will help ensure that you've got it right. If the flare leaks, cut it off and remake it.

To summarize:

- Use a good tool

- Get depth correct

- Ream properly

- Use a good assembly lubricant

- Torque properly

- Pressure test to 300+ PSIG (in most cases) and bubble test carefully

—Bryan

P.S. – A while ago, I made a video showing how to make ductless flares that won't leak. If you work on a lot of unitary or ductless equipment, you might find it useful. You can watch it HERE.

Comments

Technical Order TO 32B14-3-1-101 Operation and Service Instructions Torque Indicating Devices gives detailed use of torque wrenches and screwdrivers. Use of a crowfoot will require calculation of the required torque setting of the instrument for the required torque. The TO also shows the required torquing pattern. A search for PDF TO 32B14-3-1-101 should give you access for download. The publication has been approved for public release.

Technical Order TO 32B14-3-1-101 Operation and Service Instructions Torque Indicating Devices gives detailed use of torque wrenches and screwdrivers. Use of a crowfoot will require calculation of the required torque setting of the instrument for the required torque. The TO also shows the required torquing pattern. A search for PDF TO 32B14-3-1-101 should give you access for download. The publication has been approved for public release.

Best Cleaning Services Dubai makes your home feel brand new again. We offer high-quality House Cleaning Service Dubai that’s prompt and affordable. Our Dubai Cleaning Services are among the most preferred. Discover the joy of stress-free Cleaning Services Dubai from one of the Best Dubai Cleaning Services in the city.

Best Cleaning Services Dubai makes your home feel brand new again. We offer high-quality House Cleaning Service Dubai that’s prompt and affordable. Our Dubai Cleaning Services are among the most preferred. Discover the joy of stress-free Cleaning Services Dubai from one of the Best Dubai Cleaning Services in the city.

My understanding the flare used on a mini split is actually a 37degree and not a 45 degree. If you use a mini split kit from Diakin or CPS your torque wrench is included. Use them and your leaks will come to an end ! Promise !

My understanding the flare used on a mini split is actually a 37degree and not a 45 degree. If you use a mini split kit from Diakin or CPS your torque wrench is included. Use them and your leaks will come to an end ! Promise !

R410a flares are 45 degree, including mini-splits. The face of the flare is also slightly bigger so there is more surface area between the flare nut and the male cone. This is why mini-split manufacturers specify a 410a flaring tool. A drop of 410a oil or Nylog on the mating surfaces is key to keep from twisting the tubing as you torque it. If you do not use the oil, you run the risk of the joint “untwisting” slightly which leaves a loose flare and a leak. Torque wrenches are also a must, if you want to do the job right the first time. Never use the flare that comes on the line set, cut it off and do it right. Same goes for the flare nut on the line set, remove it and use the flare nut that comes with the mini-split. If you ever need to “flare couple” a line set, use 410a forged flare nuts for best results. The other option is to nitrogen braze the line sets together.

Enjoy the Day.

R410a flares are 45 degree, including mini-splits. The face of the flare is also slightly bigger so there is more surface area between the flare nut and the male cone. This is why mini-split manufacturers specify a 410a flaring tool. A drop of 410a oil or Nylog on the mating surfaces is key to keep from twisting the tubing as you torque it. If you do not use the oil, you run the risk of the joint “untwisting” slightly which leaves a loose flare and a leak. Torque wrenches are also a must, if you want to do the job right the first time. Never use the flare that comes on the line set, cut it off and do it right. Same goes for the flare nut on the line set, remove it and use the flare nut that comes with the mini-split. If you ever need to “flare couple” a line set, use 410a forged flare nuts for best results. The other option is to nitrogen braze the line sets together.

Enjoy the Day.

37° face angle is used for certain far east auto standards and for high pressure hydraulic connections. It’s not impossible that some group imported 410a systems would have them, but it’s not standard.

It’s more often that someone starts banging their drum and singing praises for double-flared connections than 37° flare fittings. The 37° flare angle pends up stretching the cut end slightly less for the same seal area. The cut end stretching is what leads to the double flare. They don’t seal better. The flare doesn’t stretch the cut end so it won’t propagate a crack from the cut end and develop a leak. That’s why the double flared joints can take more fluid pressure and more vibration in service. They’re less likely to leak because if the tools are poorly positioned the form a bubble then flare makes a really ugly flare, but, a double flare that looks any kind of OK will perform well. The drawbacks are the cost of the tooling and the additional time to make the double flare. In the end I suspect that fans were forced to learn to make double flares replacing brake lines but it isn’t worth the investment just for refrigeration lines.

37° face angle is used for certain far east auto standards and for high pressure hydraulic connections. It’s not impossible that some group imported 410a systems would have them, but it’s not standard.

It’s more often that someone starts banging their drum and singing praises for double-flared connections than 37° flare fittings. The 37° flare angle pends up stretching the cut end slightly less for the same seal area. The cut end stretching is what leads to the double flare. They don’t seal better. The flare doesn’t stretch the cut end so it won’t propagate a crack from the cut end and develop a leak. That’s why the double flared joints can take more fluid pressure and more vibration in service. They’re less likely to leak because if the tools are poorly positioned the form a bubble then flare makes a really ugly flare, but, a double flare that looks any kind of OK will perform well. The drawbacks are the cost of the tooling and the additional time to make the double flare. In the end I suspect that fans were forced to learn to make double flares replacing brake lines but it isn’t worth the investment just for refrigeration lines.

Seeing as there is only one service port on the vapor side of a mini split, how does one purge such a system? I was looking at adding a permanent piercing tap on the liquid line, but see that is not wise since mini splits don’t have a filter dryer to catch any debris from brazing. How about adding a flared Tee?

Also, the recommended torque specs are VERY low compared to all the manufacturer recommendations I’ve seen, by at least 20%

Seeing as there is only one service port on the vapor side of a mini split, how does one purge such a system? I was looking at adding a permanent piercing tap on the liquid line, but see that is not wise since mini splits don’t have a filter dryer to catch any debris from brazing. How about adding a flared Tee?

Also, the recommended torque specs are VERY low compared to all the manufacturer recommendations I’ve seen, by at least 20%

Hi Mike,

What do you need to purge a mini split for?

Hi Mike,

What do you need to purge a mini split for?

Just want to share how I solved my leaking issue. The outdoor unit should be sitting on a rubber mount to absorb vibration. Make sure to put refrigerant oil on the mating and sealing surface of the flare because metal expand when hot and contract when cooled. After tightening the nut to the correct specs clean it and use tire marker to make an alignment mark. So you can visually inspect if nut is getting loose. Wrap the insulation of the liquid and gas pipe separately near the outdoor unit up to the point where the pipes are close to each other. This allow the pipe to move independently from each other. Use foam spray to seal large gap on the wall to allow small movement on the pipe. R410A is very sensitive to moisture old method of purging the hose and manifold don’t completely remove air

and moisture. Buy a tool that has retractable pin that looks similar to valve removal tool, this will allow you to connect the hose of the manifold gauge to the service port without releasing refrigerant. Then use the high side for the vacuum pump to completely remove the moisture on the manifold gauge hose low side and hose going to the refrigerant tank. This is very important especially when using used hose and manifold gauge because it absorbs a lot of moisture from the air since the last time you used it. The problem by charging the system in liquid is the equipment gets wet by very hydroscopic refrigerant.

Just want to share how I solved my leaking issue. The outdoor unit should be sitting on a rubber mount to absorb vibration. Make sure to put refrigerant oil on the mating and sealing surface of the flare because metal expand when hot and contract when cooled. After tightening the nut to the correct specs clean it and use tire marker to make an alignment mark. So you can visually inspect if nut is getting loose. Wrap the insulation of the liquid and gas pipe separately near the outdoor unit up to the point where the pipes are close to each other. This allow the pipe to move independently from each other. Use foam spray to seal large gap on the wall to allow small movement on the pipe. R410A is very sensitive to moisture old method of purging the hose and manifold don’t completely remove air

and moisture. Buy a tool that has retractable pin that looks similar to valve removal tool, this will allow you to connect the hose of the manifold gauge to the service port without releasing refrigerant. Then use the high side for the vacuum pump to completely remove the moisture on the manifold gauge hose low side and hose going to the refrigerant tank. This is very important especially when using used hose and manifold gauge because it absorbs a lot of moisture from the air since the last time you used it. The problem by charging the system in liquid is the equipment gets wet by very hydroscopic refrigerant.

olympe casino en ligne: olympe casino cresus – olympe casino avis

olympe casino en ligne: olympe casino cresus – olympe casino avis

Здесь вы обнаружите лучшие игровые слоты в казино Champion.

Ассортимент игр представляет проверенные временем слоты и актуальные новинки с захватывающим оформлением и уникальными бонусами.

Каждый слот создан для максимального удовольствия как на десктопе, так и на планшетах.

Будь вы новичком или профи, здесь вы сможете выбрать что-то по вкусу.

рабочее зеркало

Автоматы работают круглосуточно и не нуждаются в установке.

Кроме того, сайт предусматривает программы лояльности и полезную информацию, для улучшения опыта.

Начните играть прямо сейчас и насладитесь азартом с брендом Champion!

Здесь вы обнаружите лучшие игровые слоты в казино Champion.

Ассортимент игр представляет проверенные временем слоты и актуальные новинки с захватывающим оформлением и уникальными бонусами.

Каждый слот создан для максимального удовольствия как на десктопе, так и на планшетах.

Будь вы новичком или профи, здесь вы сможете выбрать что-то по вкусу.

рабочее зеркало

Автоматы работают круглосуточно и не нуждаются в установке.

Кроме того, сайт предусматривает программы лояльности и полезную информацию, для улучшения опыта.

Начните играть прямо сейчас и насладитесь азартом с брендом Champion!

To leave a comment, you need to log in.

Log In