Get Tech Tips

Subscribe to free tech tips.

ACFM, SCFM, & Baseball dents

This is a VERY in-depth look at ACFM vs. SCFM and why it matters to airflow measurement from Steven Mazzoni. Thanks, Steve!

Imagine your job is to figure out how fast baseballs were traveling before they hit a sheet-rock wall. The only method you have is to measure the depth of the dent left in the wall. Suppose, at 60 mph, the ball leaves a ¼”-deep dent. At 80 mph, it leaves a ½”-dent, and so forth. No problem. All you have to do is measure the dents, and you can derive the speed (velocity).

But it’s more complicated than that. You discover that some of the balls are a bit lighter than others. Otherwise, they are all identical. What does this mean? The lighter balls leave behind a shallower dent than the heavy ones, even if they traveled at the same velocity before hitting the wall. Obviously, more is needed than just the depth of the dents. The weight of the balls must also be factored in. Suppose you can weigh the balls in addition to measuring the depth of the dent they leave. You come up with an equation that considers the ball’s weight and depth of the dent and solves for its velocity.

Something similar to the baseballs is happening when we measure airflow. To determine the airflow (cfm, or ft3/min) in a duct, all we need to find out is its average velocity (ft/min) and the duct area (ft2). Measuring the air’s velocity (duct traverse) is the tricky part. A pitot tube and manometer measure the speed of the air flowing in a duct. At a faster speed or velocity, more force is imparted to the column of water in the manometer. The pressure difference (velocity pressure or VP) determines the air’s velocity in feet/minute.

However, like the baseballs, air’s density isn’t always the same. Thus, the force it imparts to the column of water when traveling at a given velocity changes if its density changes. “Heavy” air will lift a column of water to a higher level (velocity pressure, in inches of water) on a manometer than “light” air will, even though it's moving at the exact same velocity. Thus, the velocity pressure and the air’s density must be factored in before we can determine its velocity.

What factors determine the air’s density? Mainly its temperature and the barometric pressure. Warm air is lighter (less dense) than cold air. Air at higher barometric pressures near sea level is denser than air at lower pressures (high altitudes). The air’s moisture content also plays a minor role. Moist air (high humidity) at a given temperature is lighter than dry air at the same temperature.

The flow of air (volumetric) is usually expressed in cfm (ft3/min). To be more specific, actual cfm (ACFM) and standard cfm (SCFM) are used. ACFM & SCFM have been defined as follows:

Air is at “standard conditions” when its density is @ 0.075 lb/ft3. We can thus conclude a couple of key points. First, if the airflow measurement is taken at or near standard conditions, the ACFM and the SCFM will have the exact same value. Second, if the reading were taken on air at a significantly different density, ACFM and SCFM would have two different values.

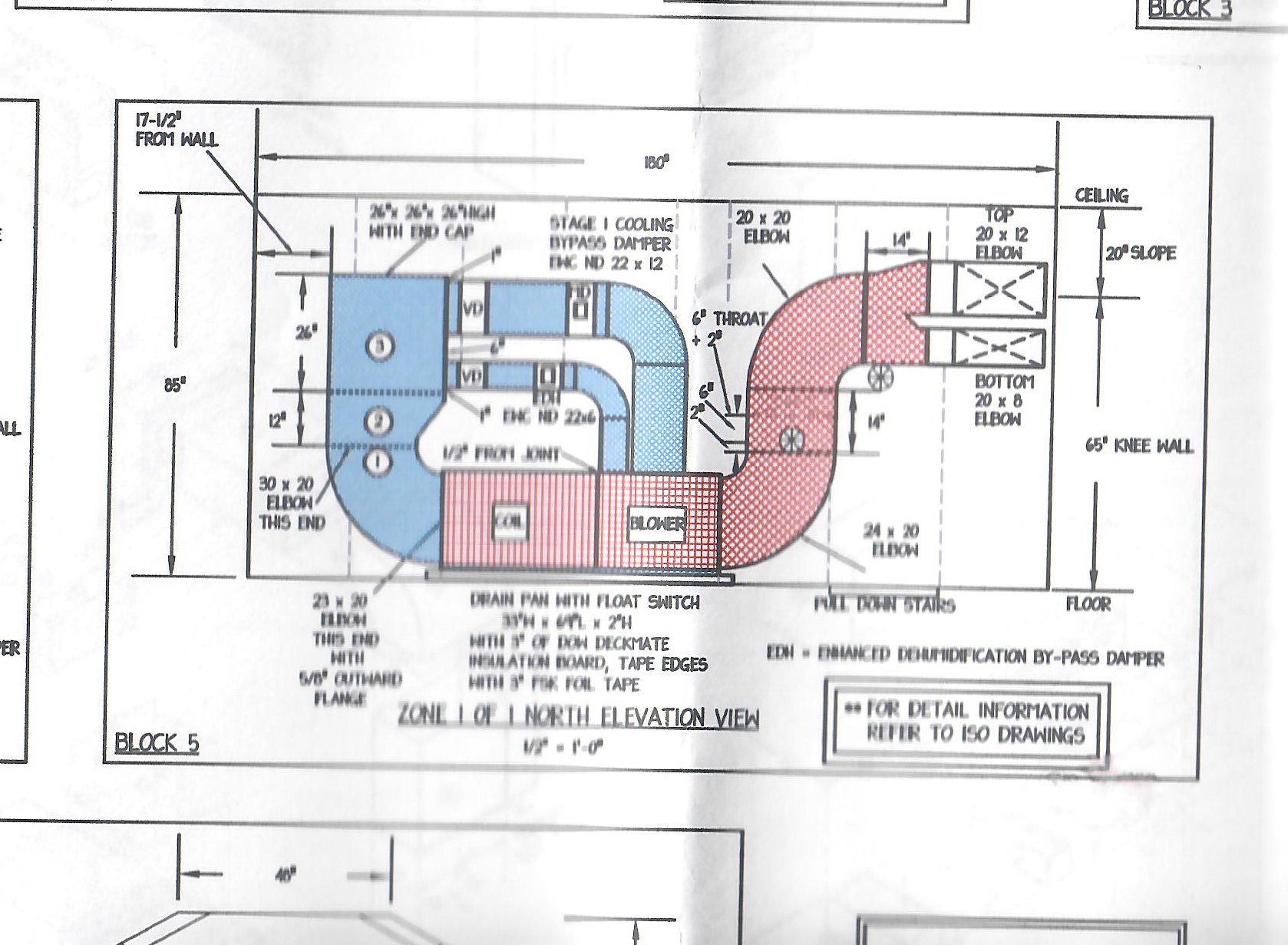

Let’s work through an example duct traverse at a high elevation and temperature to show how to determine ACFM & SCFM. Suppose a 4-point duct traverse has been taken at the following conditions. A pitot tube was used to obtain velocity pressures (VP), but these have not yet been converted to velocity (ft/min). Let’s keep it simple and assume a 1.0 ft2 duct.

| Elevation: | 4,000 ft |

| Barometric pressure: | 25.84” Hg |

| Duct temperature: | 120°F |

| Duct area: | 12” x 12” = 1.0 ft2 |

| Actual air density: | 0.059 lb/ft3 |

| Standard air density: | 0.075 lb/ft3 |

| Actual velocity pressure (VP) readings: | 0.020” WC |

| 0.025” WC | |

| 0.030” WC | |

| 0.035” WC |

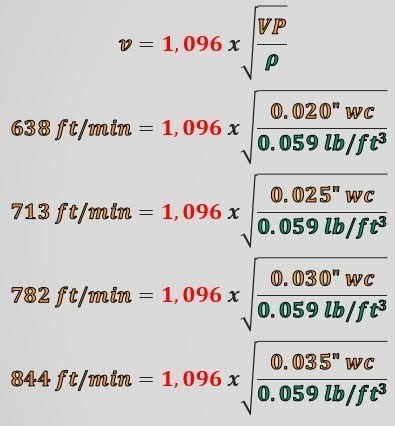

Now, what do we do with these four velocity pressure readings? We need to convert them to velocity using one of the equations below. The “4,005” equation is only valid for air at standard density. The “1,096” equation works at any density.

Here is where it gets interesting. Which density should we use to convert the VP readings to velocity to determine ACFM & SCFM? The actual density (0.059 lb/ft3), or standard density (0.075 lb/ft3)? We’ll explore two options.

- Option 1: Calculate the actual average duct velocity using the actual density of the air measured.

Then, multiply average velocity by the duct area in ft2. The result will be in ACFM.

Calculate ACFM Using Option 1:

| 0.020” WC = | 638 ft/min |

| 0.025” WC = | 713 ft/min |

| 0.030” WC = | 782 ft/min |

| 0.035” WC = | 844 ft/min |

| Avg = | 744 ft/min |

- Determine SCFM for our example using one of these two methods:

- Method A: Determine the mass flow rate of the ACFM. From that, determine what volumetric flow at standard conditions would result in the same mass flow. The result will be in SCFM.

- Method B: Multiply the ACFM by the ratio of the actual density to standard density. The result will be in SCFM.

- Method A & B both result in @ 585 SCFM.

- Option 2: Even though we realize the actual density at the traverse was not standard, calculate using the standard density. Multiply by the area in ft2. Then take the result and apply a correction factor to determine ACFM & SCFM. Calculate velocity and flow using the same VPs from the non-standard density traverse but using the standard density 4,005 formula:

| 0.020” WC = | 566 ft/min |

| 0.025” WC = | 633 ft/min |

| 0.030” WC = | 694 ft/min |

| 0.035” WC = | 749 ft/min |

| Avg = | 661 ft/min |

- Is this 661 “cfm” the ACFM? No. Is it the SCFM? No. Obviously, it falls in between the 744 ACFM and 585 SCFM we calculated above. What is it, then? It is a value that, when corrected, can get us to the true ACFM & SCFM.

- Determine a unique correction factor for our example as follows. Notice the square root function:

- Now what? Use this correction factor to convert the “uncorrected” 661 cfm to ACFM as follows:

- Next, use the same correction factor to convert the “uncorrected” 661 cfm to SCFM as follows:

Conclusions: Consider the type of instrument you are using to measure the differential pressure coming from a pitot tube. Velocity pressure readings from inclined manometers and simple differential pressure instruments will need the correct math applied. Electronic ones may be able to correct for local density and display the actual velocity.

- Both Option 1 & 2 resulted in the same ACFM & SCFM values.

- In Option 1, we used the actual local density to determine the actual average duct velocity and the ACFM. From the ACFM, we calculated the SCFM based on either the mass flow (Method A) or the ratio of actual density to standard density (Method B).

- In Option 2, standard density was used to calculate a “reference cfm.” This reference cfm did not reflect reality but was used to calculate ACFM & SCFM. A correction factor had to be calculated (square root of the ratio of the two densities) and used to convert the reference cfm to ACFM and SCFM. This method is similar to assuming all the baseballs are the heavy ones and calculating a reference speed based on that incorrect premise. Then, you must correct the result based on the actual weight of the baseball.

- To avoid confusion, it seems best to use Option 1 and Method B when working with air under non-standard conditions. At least then, the calculation gives you the ACFM directly. SCFM can be calculated easily based on the ratio of the two densities. No other correction factors are needed.

—Steven Mazzoni

HVAC/R Instructor

Comments

Nice breakdown from Steve! Loved reading the article! -ernie martinez

Nice breakdown from Steve! Loved reading the article! -ernie martinez

pharmacie en ligne france fiable: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne pas cher pharmafst.com

pharmacie en ligne france fiable: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne pas cher pharmafst.com

pharmacie en ligne pas cher: pharmacie en ligne pas cher – pharmacie en ligne pharmafst.com

pharmacie en ligne pas cher: pharmacie en ligne pas cher – pharmacie en ligne pharmafst.com

Acheter Kamagra site fiable kamagra 100mg prix or kamagra 100mg prix

http://www.google.co.zm/url?q=https://kamagraprix.shop kamagra gel

[url=http://ibbs.ci123.com/notlogin.php?backurl=http://kamagraprix.shop]kamagra gel[/url] kamagra pas cher and [url=https://www.support-groups.org/memberlist.php?mode=viewprofile&u=359710]kamagra oral jelly[/url] kamagra 100mg prix

Acheter Kamagra site fiable kamagra 100mg prix or kamagra 100mg prix

http://www.google.co.zm/url?q=https://kamagraprix.shop kamagra gel

[url=http://ibbs.ci123.com/notlogin.php?backurl=http://kamagraprix.shop]kamagra gel[/url] kamagra pas cher and [url=https://www.support-groups.org/memberlist.php?mode=viewprofile&u=359710]kamagra oral jelly[/url] kamagra 100mg prix

https://pharmafst.shop/# pharmacie en ligne pas cher

https://pharmafst.shop/# pharmacie en ligne pas cher

pharmacie en ligne fiable Pharmacie sans ordonnance or pharmacie en ligne france pas cher

http://www.google.ki/url?q=https://pharmafst.com pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance

[url=https://image.google.com.sb/url?q=https://pharmafst.com]Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable[/url] pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance and [url=http://80tt1.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=3239435]Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable[/url] Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe

pharmacie en ligne fiable Pharmacie sans ordonnance or pharmacie en ligne france pas cher

http://www.google.ki/url?q=https://pharmafst.com pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance

[url=https://image.google.com.sb/url?q=https://pharmafst.com]Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable[/url] pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance and [url=http://80tt1.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=3239435]Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable[/url] Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe

acheter kamagra site fiable: kamagra pas cher – acheter kamagra site fiable

acheter kamagra site fiable: kamagra pas cher – acheter kamagra site fiable

acheter kamagra site fiable: kamagra pas cher – acheter kamagra site fiable

acheter kamagra site fiable: kamagra pas cher – acheter kamagra site fiable

cialis prix: Tadalafil achat en ligne – Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher tadalmed.shop

cialis prix: Tadalafil achat en ligne – Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher tadalmed.shop

casino olympe: olympe casino cresus – olympe casino cresus

casino olympe: olympe casino cresus – olympe casino cresus

To leave a comment, you need to log in.

Log In